Annie M Snyder's Still Life, or Theology in a Basket

Is it bigger or smaller than a breadbasket? A metaphysical game of 20 questions, and scores of Concord grapes.

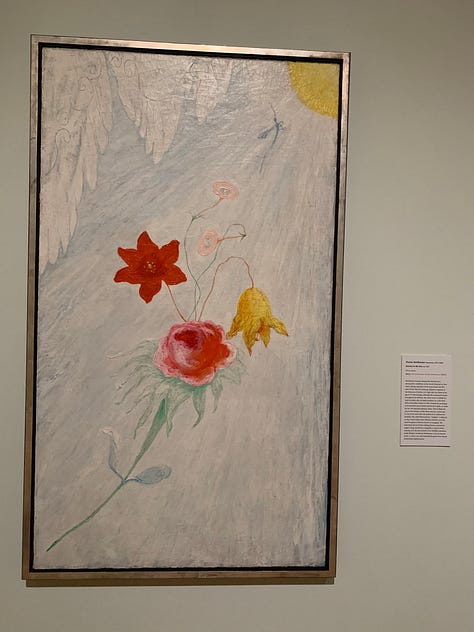

I recently enjoyed a weekend in Santa Barbara, California, pretending I was in a glamorous foreign land with an unfavorable exchange rate, and visited the Santa Barbara Museum of Art for the first time. What a jewel-box of a museum and a bargain at $10! I learned about several new-to-me artists, and was also struck by the higher than usual ratio of women to men artists. I looked closely at several artworks that I would love to share with you in future posts, such as a lady with a plump chicken sculpture from Tang dynasty China, Florine Stettheimer’s trippy/sort-of-abstract Journey to the Sun (1927), and a small, demure, intimate Rauschenberg (whose works are not usually small nor demure nor intimate), among other things. Stay subscribed for these! And leave a comment voting which one you want to hear about first:)

One of the works that drew me in was called Still Life: Basket of Grapes (1890’s) by Annie M. Snyder (American, 1852-1927), an artist I had never heard of before. This very simple yet riveting little still life is in the nineteenth-century American vein of trompe l’oeil (French for “fool the eye”) painting, which is characterized by an extreme closeness to representing objects as they appear, at life-size, with gentle daytime lighting, and with hidden brushstrokes. Usually, as here, the artist chooses humble, quotidian American objects (that is, not exotic or foreign). As the wall lab text said, Annie Snyder is an critically under-investigated artist, but her technical painting skills are quite impressive.

Figure 1. Annie M. Snyder, Still Life: Basket of Grapes (1890’s)

Figure 2. My photo from the museum, to give you a sense of scale

Compared to the photo I took and the one on the museum’s website, the painting in real life has more depth, personality, and gradations of color, reminding us all that seeing artwork in person makes a big difference even with the best reproductions available. A close looking of this painting shows that Snyder was able to skillfully replicate a genuine appreciation for beauty found in the simplest of objects, and I think her choice of grapes in a breadbasket also has deeper theological implications.

The painting seems to be a mere bagatelle of simplicity; it depicts nothing but a plain wooden oval basket, filled to overflowing with bunches of marvelously luscious Concord grapes, set on a surface of medium gray, with a medium gray background. I was reminded of a small painting of Blackberries (c. 1813) by the American painter Raphaelle Peale, which also is a simple group of dark fruit against a grey background. But in Peale’s Blackberries, each little berry is at a different stage of ripeness, and gets its own moment, even its own little personality. In Snyder’s painting, by contrast, the grapes are in such tight bunches and so uniform, they are more like a crowd, all glistening together under their “waxy bloom” (the coating on the outside of the Concord grape).

Figure 3.

The basket is full of fruit, with a couple stems but no leaves visible; the grapes are jumbled and heaped in uncountable abundance. They are active, living, almost as shiny as roe glistening on a plate; unlike more rare caviar, these are just a common American grape. Still, they have a refined quality, because Snyder has observed the way the grapes’ skins reflect the light, with a shine under the delicate dusky matte bloom. The careful, life-size rendering of the beautiful fruit drew me in, the way the fruit painted by the ancient artist Zeuxis attracted hungry birds. That’s a famous story from Pliny the Elder that, as a trompe l’oeill painter, Snyder surely would have known.

One thing to keep a lookout for in still life paintings in general is evidence of a human hand, which often points to the passage of time. With these grapes we can see where fingers touched them—where the bloom has been worn away to a shine, the grapes were once held in the palm of a hand before being placed in the basket. The basket itself is the other evidence of human intervention. This simple oval basket was made of the strips of the thinnest poplar wood. Its gray white contains a tinge of pink brought out because of the juxtaposition with the duller medium gray of the table and background. To construct the basket, the wooden strips would have been water-soaked and bent, then overlapped and nailed together with tiny brass nails. Though simple, the construction shows careful craftsmanship and patience. The handle arching over the top defines the relatively shallow depth of the painting. The basket, with its clean and visible construction, points to the Shaker aesthetic, with a beauty in simplicity for which Shaker artisans were famous. I immediately thought of the hymn “Simple Gifts,” that other great Shaker contribution to Americana.

Of course, any artist working in late 19th century America would also have been acutely aware of the theological implications of grapes as the source for sacramental wine. The temperance movement was in full swing, and a Dr. Thomas Welch, a Methodist who wanted to provide a non-alcoholic wine for communion, developed a way to produce grape juice out of Concord grapes that would not ferment. It was called “Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Wine” and the company’s name changed to Dr. Welch’s Grape Juice in 1890; the company’s presence at the1893 Chicago World’s Fair popularized the drink, right around the time Snyder painted this little still life. Welch’s is the name synonymous with grape juice to this day, as you probably know.

Concord grapes in a Shaker basket must have had a theological and probably temperance-movement overtones for her American audience. The basket itself is the size and shape of a loaf of bread, the classic unit of measurement in the American road trip game 20 questions (is it bigger than a bread basket?). In all Christian traditions, bread and wine together immediately allude to the sacrament of the body of Christ. Even without knowing anything about Annie Snyders’ particular religious background, I am confident she would have been painting under this assumption, even more than knowing about Pliny the Elder’s story of Zeuxis. It is conceivable that she made her refined depiction of these grapes into a worshipful experience. Even the happy jumble of grapes crowded together allude to their communal quality, as though they are all one in the body of Christ (1st Corinthians, 12: 12-27).

Thank you, Santa Barbara Museum of Art! Remember: VOTE in the comments for the first to appear: Tang dynasty Lady with Chicken, Trippy trip to the Sun, or Demure Rauchenberg!

Bonus content: The gray indefinite neutral background promotes the subject by being utterly neutral in hue, value, and intensity. Artists would paint the inside of their studios this medium gray tone, in order for the colors in their painting to be as true to themselves, without being influenced by surrounding color. An ideal studio also has windows facing north, so that the light be unchanging and gentle (at least in the northern hemisphere). I was lucky enough to visit Paul Cezanne’s studio in Aix-en-Provence a couple of years ago; it faces north and is painted the same medium gray. Here’s a still life by Cezanne—a totally different style but within a decade of Annie M Snyder’s— and a link to a video of Cezanne’s studio—take a little trip to Provence this Friday afternoon!

https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/video/cezanne-still-life-studio.html

Figure 4. Paul Cezanne, Still Life with Milk Jug and Fruit, (c. 1900), Oil on Canvas, 45.8 x 54.9 cm (18 1/16 x 21 5/8 in.). National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Artwork above:

Figure 1. Annie M. Snyder (American, 1852-1927), Still Life: Basket of Grapes (1890’s). Oil on academy board, 14 x 20 in. (35.6 x 50.8 cm). Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara

Figure 2. Snyder, Basket of Grapes, photo by author.

Figure 3. Snyder, Basket of Grapes, and Raphaelle Peale, Still Life with Blackberries, (1813). Oil on Canvas, 18.4 cm (7.2 in) x 26 cm (10.2 in). de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Thanks to my old friend Adam, who told me about Welch’s Grape Juice and Methodist history long ago.

Other sources:

https://www.umc.org/en/content/communion-and-welchs-grape-juice

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Bramwell_Welch

https://www.welchs.com/our-story/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concord_grape#:~:text=The%20Concord%20grape%20was%20developed,one%2Dthird%20Vitis%20vinifera%20parentage.

Another revelation.