Continuous Narration, and Ugo da Carpi's Sacrifice of Abraham, Part 2

Pair with a listen (ironically) to Bach's “Sheep May Safely Graze." Plus another painting from the Sienese Renaissance: watch for friendly pilgrim centaurs on your next hike through the forest.

Previously on The Vivid Eye:

[Sidebar: You know when the deep voice comes on to introduce a second installment of the same episode of a TV show, that was continued from last week? I just learned that TV writers call these moments “previously ons.” Cute, right? This phenomenon seems to be continuing even now in the binge-able Netflix era: it helps the viewer just joining in, AND helps the writers to fill in extra time, if needed. I can appreciate this. Now, back to our scheduled program.]

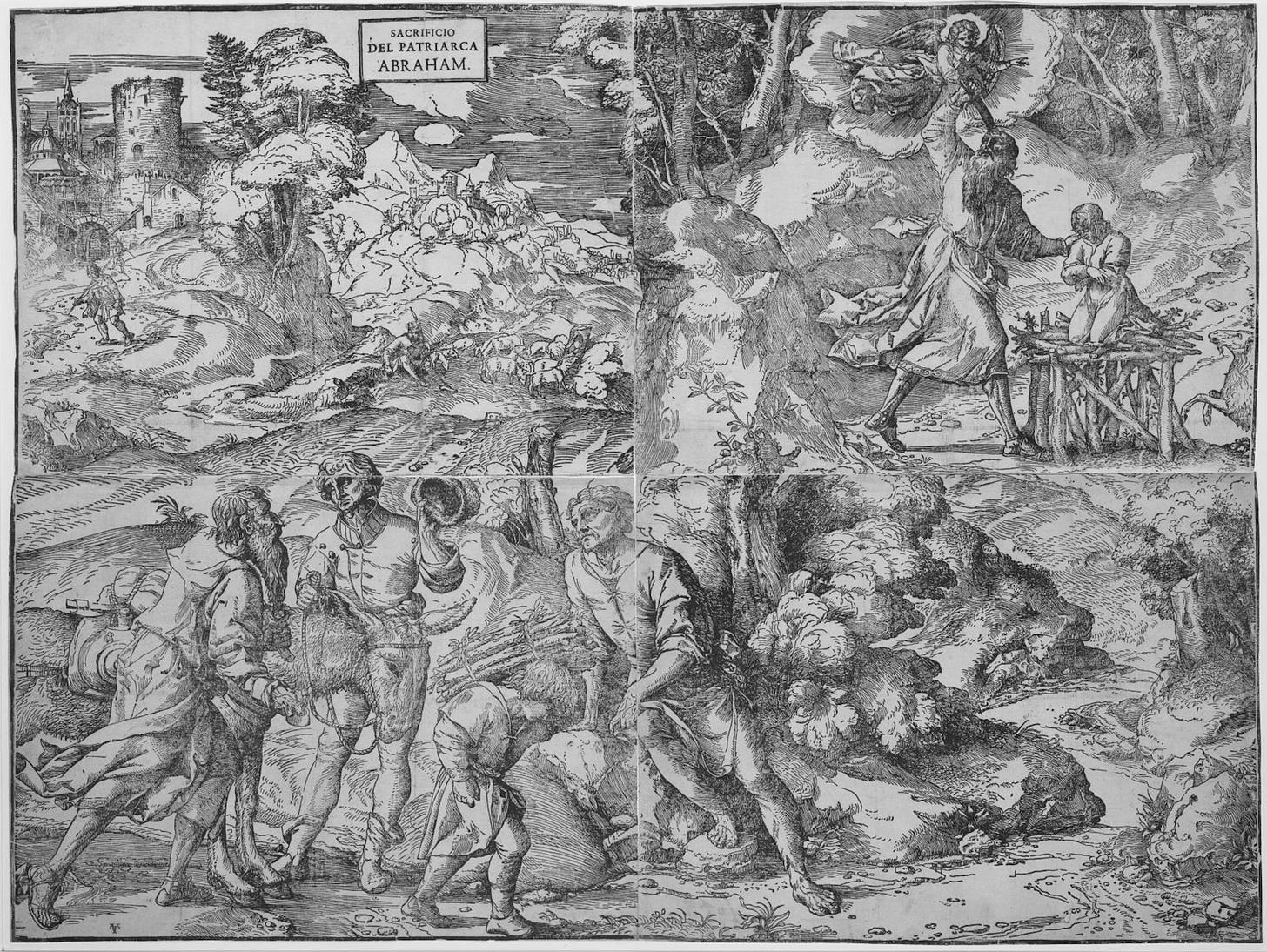

Ugo da Carpi, after Titian, The Sacrifice of Abraham (c. 1511-1515), woodcut on four sheets, total size 80 x 107.6 cm (31 1/2 x 42 3/8 in.)

Last week we explored the joins between four papers in the large print of the Sacrifice of Abraham by Ugo da Carpi, observing that the upper right quadrant was created first as a stand-alone single-sheet print. The less successful moments at the edges—the cut-off hat! The abrupt landscape!—make me think that the expansion was a somewhat rushed job to be able to sell a larger, and thus more expensive print, more quickly. More successfully, the expansion allows an extension of the narrative. When Ugo expanded the print into a larger pictorial field over four sheets, he was able to include the “prequel” to the climactic moment by adding in the two youths who don’t usually appear in representations of this story. If you need a refresher on the biblical source or on my observations, feel free to turn back to the previous post of November 1, 2024.

The larger print over four sheets allows us to read the narrative clearly and to recognize the Abraham and Isaac characters—now appearing twice, in both the climax of the story on the upper right and in the prequel at the lower left—in what is called continuous narration. Continuous narration is when the same character appears twice in the same pictorial space, but in different moments of the story. To make it work, the artist makes them recognizable by their same physiognomy and outfits. The first work I remember seeing with continuous narration was this sweet little painting then attributed to Sassetta from Renaissance Siena in the National Gallery, the Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul, now attributed to the Master of the Osservanza or Sano di Pietro.

Master of the Osservanza or Sano di Pietro (previously attributed to Sassetta), The Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul, c. 1430-1435. Tempera on poplar panel, 47x33.6 cm, 18 1/2 x 13 1/4 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Saint Anthony Abbot is a hermit who has heard about a fellow-minded hermit, Saint Paul, and decides to go on a long trip to pay him a visit. He begins his journey at the upper left on the rocky path through the forest. Actually, it’s not the beginning of his walk, since he is already too warm and has taken off his pink cloak. He carries it with a second stick on his shoulder, resembling the classic cartoon runaway/hobo bindle look with all worldly belongings tied in a bandana. Our eye starts in the back with him and follows the backwards S-shaped path to trace his journey. Recognizable by his pink and blue-grey cloaks and beard, Saint Anthony is shown a second time, mid-journey; and whom should he meet but a centaur, no big deal.

They seem to be having a nice conversation, with St Anthony gesturing as they speak. The centaur might represent the conversion of a pagan past to Christianity, since he carries a palm frond, the symbol of a pilgrim. In any case he seems ready to head off on his own pilgrimage again, with one horse-leg lifted. The trees conceal the rest of his horse-body, conveniently enough for the artist (it’s haaard to draw horses! Let’s just disappear the rest of him behind trees:), and anyway the main purpose of this scene is the next moment. We see Saint Anthony in the foreground, embracing Saint Paul. In their excitement at meeting, both hermits have dropped their walking sticks on the ground, their halos warmly overlapping behind both of them as they stretch their arms widely around the other. Their hug forms a rounded triangle, echoed by the shape of the mouth of St. Paul’s cave and by the background hills.

I love the uniformity of the tufts of the trees, like plumy celosia flowers but green, textured with tiny dots of paint, all rising from smooth, stem-like trunks. The heavenly gold sky with punch-work around the edge (and in the haloes), and the pinkish afterthought-maybe-church in the background over the gold leaf endows a holiness to the landscape. It’s a fantastical setting, a better world than ours, where hermits embrace in a safe and splendid wild landscape—in which you might even meet a centaur pilgrim on your journey to visit a friend.

Now back to the continuous narration in The Sacrifice of Abraham. We recognize Abraham not only by his beard and robe but also by the similarities of pose. Abraham in the upper right (created first, remember) has his robes waving dramatically behind him, in folds that are another reminder of Dürer’s influence. He twists with his right leg in front, his body corkscrewing up from his back left toe.

In the lower left sheet, he is leaning forward as he strides, where Ugo has reused his lower half, recycling the pose. This time, though, his right toe pushes off and his left leg is bent in front. His robes rise out again behind him, less about drama this time and more for forward movement. Isaac has some differences in proportion and haircut, but he is basically an attribute of Abraham, the sidekick who makes the story recognizable, so he doesn’t need to be as identical. As with The Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul, the continuous narration allows us to infer that a period of time has passed between the two appearances of Abraham and Isaac.

The other commercial advantage of expanding the Sacrifice of Abraham into a larger pictorial field over four sheets, was to include actual verdant fields and a deeper landscape, in the upper left quadrant especially.

This type of pastoral scene, with rolling green hills, lounging shepherds, and grazing sheep, was extremely popular in the moment of early sixteenth century Renaissance Venice. This is a big topic and the subject of entire books, but in brief it was a moment influenced by the literature of antiquity such as Virgil’s Giorgics, the Ecologues, and the idea of Arcadia. Being able to include this theme updated the Sacrifice of Abraham to a more fashionable story, letting the lambs and ram mentioned in the biblical story become an excuse to bring in the more secular obsession with shepherds and landscape.

The two youths not only connect the four sheets together with their bodies going over the join, they also partake in this pastoral theme. The hat-doffing youth holds the donkey’s reins and is dressed in more modern attire; he and his lounging friend are more like stand-ins for the Renaissance viewer who can imagine himself partaking in this idealized landscape AND be a witness to the holy story. In the upper left quadrant Ugo included a seated shepherd and his flock; a couple of wanderers on a path up to a fortified town on the left, with staffs and a similar hat; and, further back, another hilltop fortification and a mountain range. The pastoral scene would have been one of the selling points of this large print—something not lost on Ugo da Carpi or the publisher Benaglio. The two youths thus provide the formal and thematic connection that bring all four of the woodcut’s papers together.

Oh—I promised to come back to why there is a goat, instead of a ram, who comes in prancing and rearing in the upper right quadrant. The story goes: And Abraham lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold behind him a ram caught in the thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering in the stead of his son. But this animal is neither a ram, nor in a thicket caught by its horns. It has a clear goat shape with a beard and cloven hooves. For the goat appearance, I have two semi-opposing theories. (Remember this sheet was also made first, before turning the scene into a pastoral idyll, otherwise it probably would have been a ram or sheep.) One theory is religious, in that the goat references other scriptural moments. It could refer to separating the sheep and the goats (the goats get the worse end of the deal, like this goat about to be sacrificed) as in Matthew 25, making it a New Testament and therefore more Christian reference. Another scriptural reference is the ancient Israelite “scapegoat” idea—that the sins of the community would be transferred to a goat and sent into the wilderness as in Leviticus 16, kind of like a substitute sacrifice, as was the ram for Isaac. This was another Christian typological reference, wherein Christ becomes the scapegoat by taking on the sins of the world.

But it’s so unusual not to just take the simpler route and include a ram in this story, as is clearly mentioned. So my second theory is that the goat shows Titian’s particular streak of humor. Remember, Ugo da Carpi was the woodcutter of the print, probably working here from a drawing by Titian. Titian could make movingly pious works, but he had an irreverent streak, and sometimes puts in moments of subversion that make you think, hey, he can’t be serious—really?! I’ll come back to this idea when I tell you about the moments of humor in his long print the Triumph of Christ, and about the defecating dog in his Drowning of Pharoah’s Army in the Red Sea. Yes, really! a pooping dog—it’s kind of like the “taunting Frenchman” moment in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which humor Titian really would have appreciated.

Therefore, definitely subscribe (it’s free!) so you don’t miss learning about the humor in those artworks in the coming months!

Tell your friends to subscribe, and your enemies, which will turn them into friends.

AND: If you have questions, about the artworks or a term you’d like me to explain further, please ask in the comments! I’d be so happy to answer your questions, big or small!

👍