Cut into Quadrants: The Sacrifice of Abraham by Ugo da Carpi after Titian, Part 1

Hold onto your hat! The edges or seams might tell you a lot about a print. Menu: lamb en flambé with a side of asparagus.

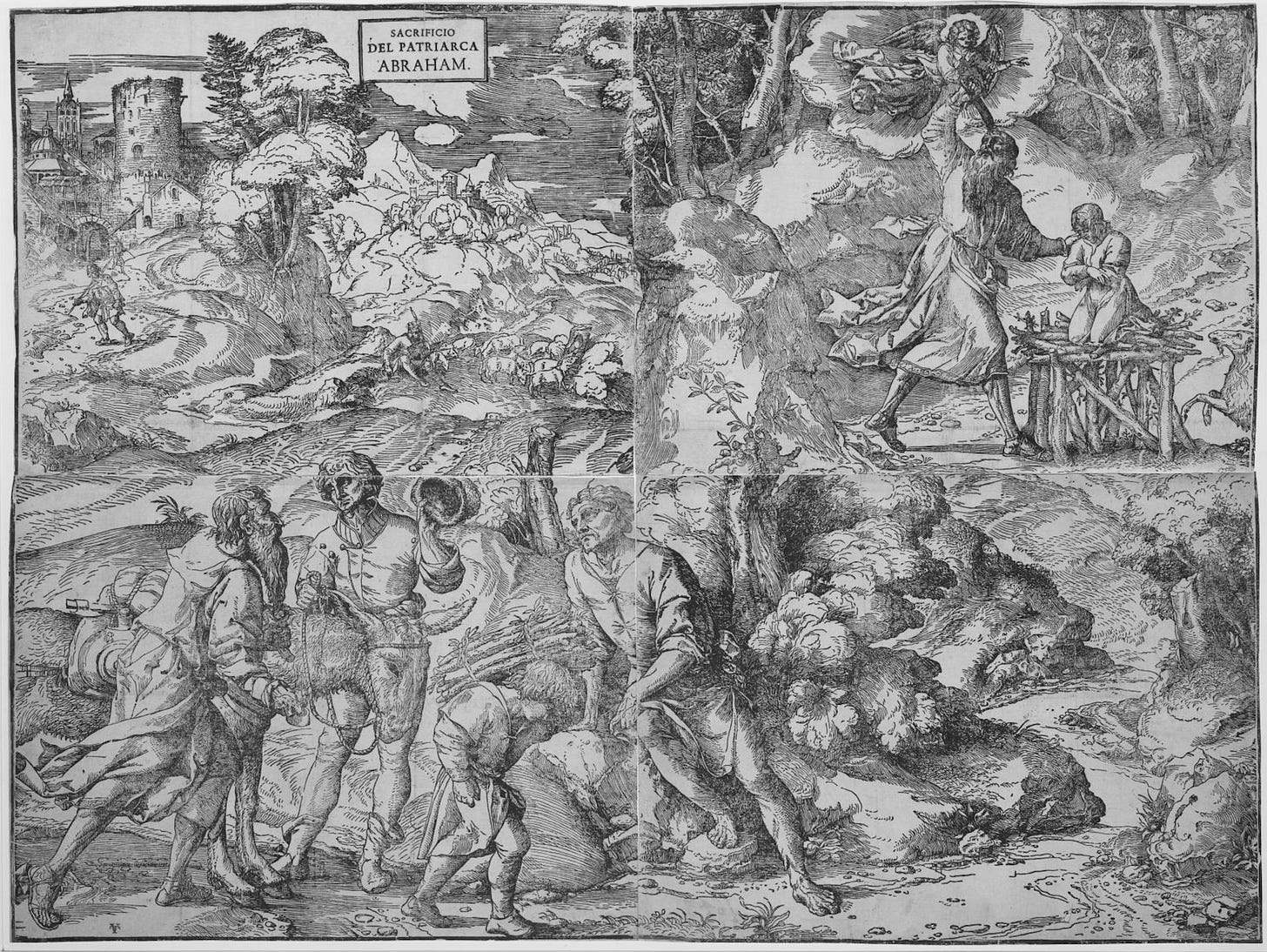

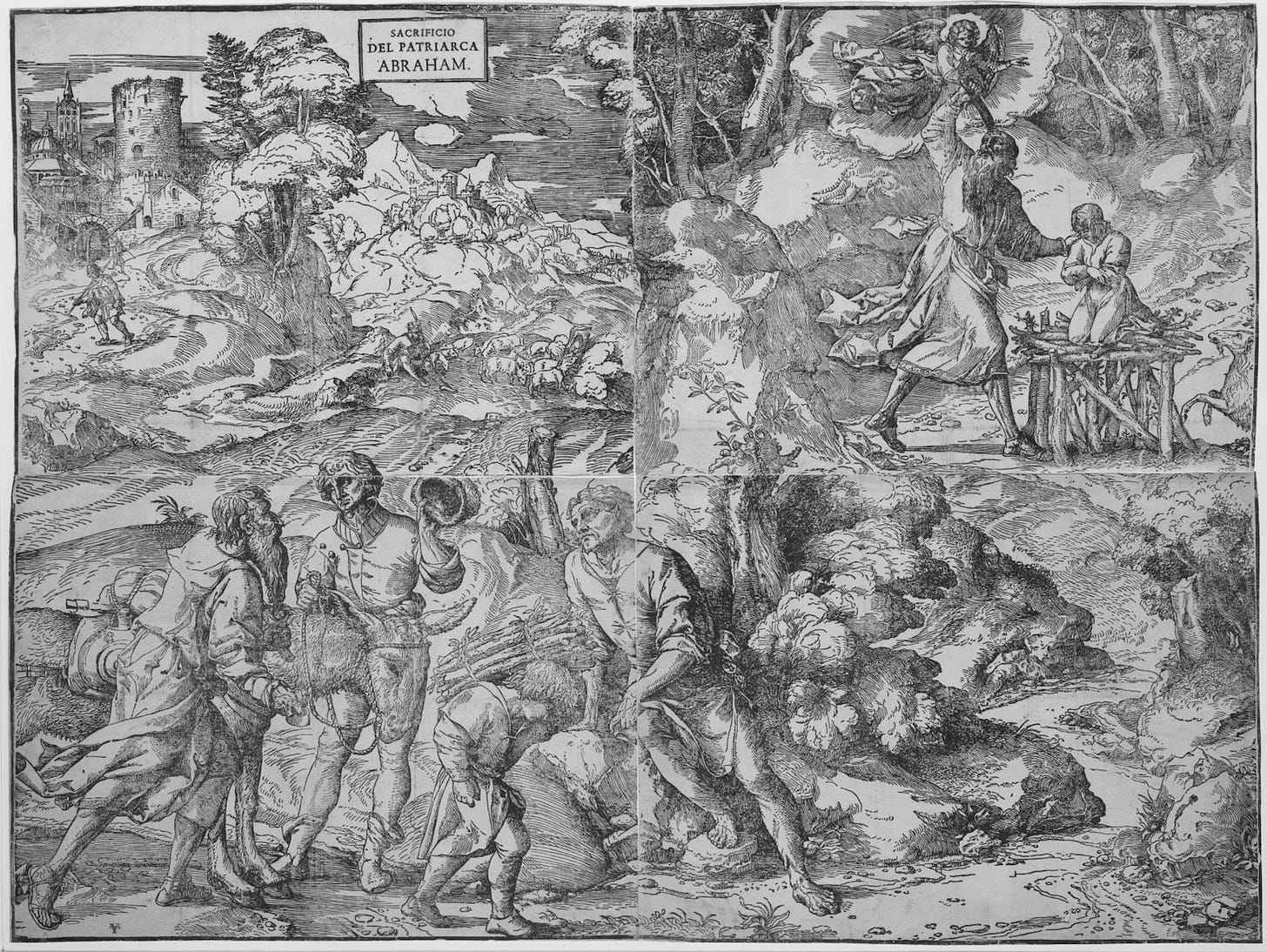

Figure 1. Ugo da Carpi, after Titian, The Sacrifice of Abraham (c. 1511-1515), woodcut on four sheets, total size 80 x 107.6 cm (31 1/2 x 42 3/8 in.)

The question: when printing a scene across more than one paper, how can you convincingly carry an image across the break where the papers meet? In the Renaissance, there were three solutions to this problem, and the two I’ll focus on today are, first, what I call using non-significant representation to disguise the join; and second, flaunting your skills as a carver and printer by carrying significant representation over the join. I’ll come back to the third—placing a pilaster (a flattened column, usually against a wall) printed or pasted, as a framing device next to or cut-and-pasted over the edge—in a future post, since it doesn’t apply much today. In today’s scene, Ugo da Carpi uses both #1 and #2, in a four-paper print, in order to include both the dramatic moment when the angel stops Abrahams knife AND the “prequel” of the Biblical story—in order to bring in fashionable pastoral flavor.

The first ever print over two sheets was Andrea Mantegna’s Battle of the Sea Gods (1470-75, certainly before 1481), which I discussed earlier—see my post dated August 16, 2024. Mantegna disguises the break in paper with busy but simple textures of rushes and reeds, thus using non-significant representation, where the eye would be less bothered if not every blade of grass matched perfectly.

Andrea Mantegna, Battle of the Sea Gods, Engraving over two sheets. Detail of join, below.

Mantegna still gives us tension at that join, and connection between the two halves of the print, to create a single, unified, long image: for example, the sea nymph’s elbow and thigh graze the edge of the paper, but in turning and looking towards the left side, she links the action on both halves of the print. The windy fabric she holds continues a tiny bit over the edge. And on the left sheet, the sea serpent-like tail winds and coils upward, as though twining itself around a pole, again very close to the paper-join. The scales, tailfin and scarf textures carry over the edge but still allow Mantegna to avoid having to match something like a face or a body, instead filled with patterns of the marshy reeds and fishy scales and hatched shadows.

In this week’ print (Figure 1, above), a large four-sheet print of the Sacrifice of Abraham by Ugo da Carpi, the edges show the artist's decision to use both non-significant and significant representation over the edge—at times more successfully than at other times. We can see how the joins between papers support the idea that the print started as a composition on a single sheet, and then Ugo da Carpi expanded it to four. That first composition was the upper right quadrant, showing the most famous and climactic moment of the Old Testament story found in Genesis, where an angel intervenes before Abraham can sacrifice his only son Isaac (I’ve included the verses at the end of this post, if you are unfamiliar with the story). We’re setting aside the questionable ethical, moral, and psychological parts of the story as well as the Christian typological parts; suffice it to say that it’s got no shortage of drama!

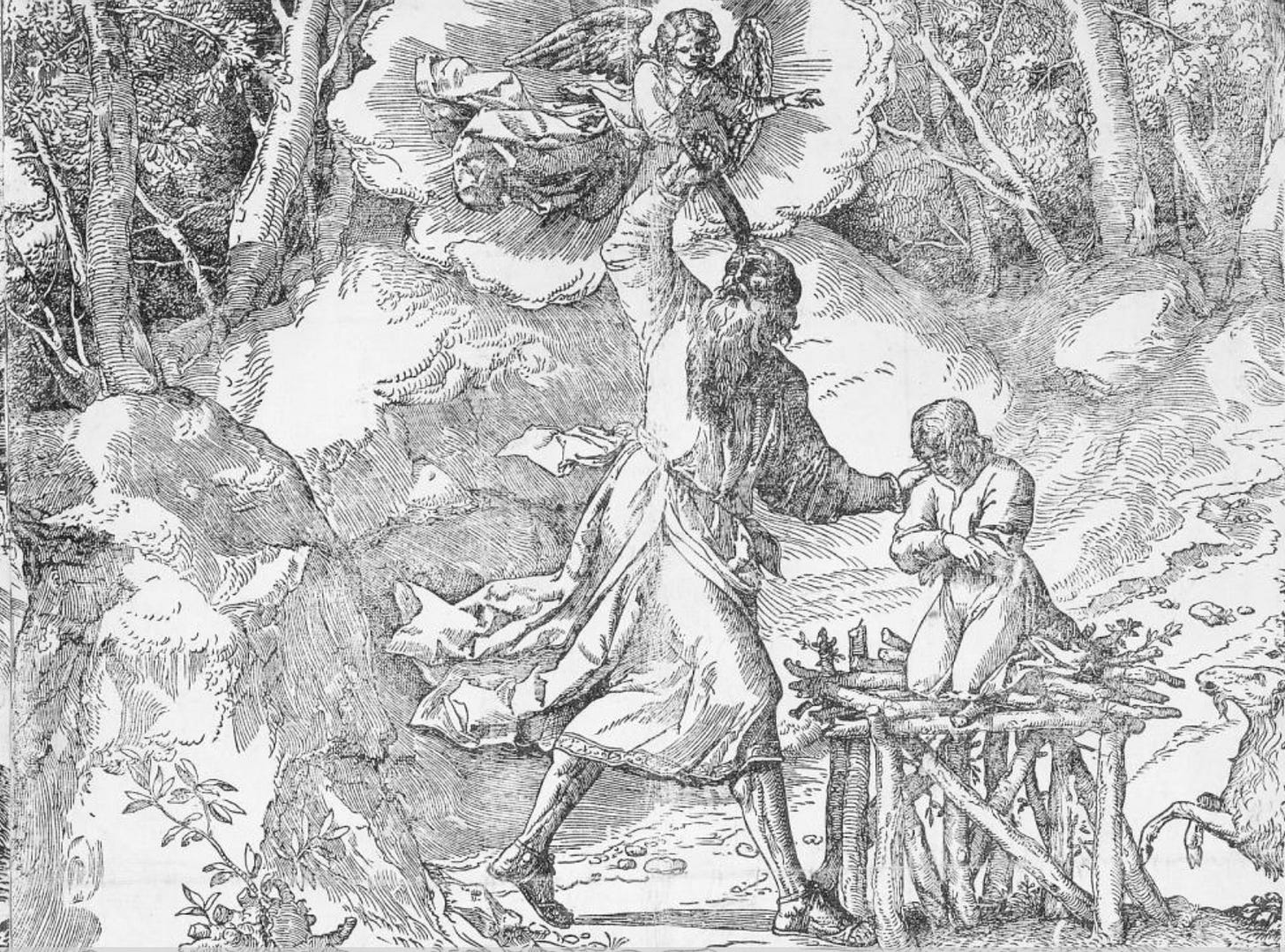

Detail of Figure 1, Upper right sheet.

This scene can easily stand on its own. Centered in the sheet, Abraham raises his knife—really a short sword—as though he will bring it down on his son, who kneels with head bowed and arms folded on an extremely rustic altar, at the moment the angel stops his hand. Engineers, feel free to chime in, but I think this altar needs more cross-beams. It doesn’t seem to be able to support the weight of even a small child, or the huff and puff of the Big Bad Wolf coming after the second of the Three Little Pigs. Did we learn nothing about structural engineering from that story, Abraham?! Bricks! Use Bricks! Or at least more triangular construction! But I think the haphazardness of the altar is part of the story after all, a small miracle to be followed by the bigger miracles of the appearance of the angel and the ram (yes, the ram here is a goat. More on that next week).

Ugo da Carpi may have been working with the much more famous artist Titiano Vecellio, or as English speakers know him, Titian. Titian probably provided him with drawings. The twist of Abraham’s body, the composition, the forest scene surrounding him, all point to Titianesque ideas. Ugo also borrowed the angel from a print by Dürer (see my post on August 30), the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Notice how the raised sword and grip of one of the horsemen was modified to become Abraham’s lifted hand and knife.

Albrecht Dürer, detail from Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, c. 1497-8. Woodcut.

Ugo da Carpi was quite a talented artist and carver of woodblock prints, especially in chiaroscuro printing, which was a technique using more than one block to create shading. That’s not the case here, but I’ll certainly be writing a future post on the chiaroscuro technique, an example of which was featured in my introductory post. In engravings, as in the examples in my earlier posts on Mantegna and Dürer, whatever lines you carve into the copper plate would become the lines printed on the paper. With woodblock prints it’s the opposite: wherever you carve away the wood, that becomes the negative space, the white of the paper, and whatever you don’t carve away becomes printed. So here, all those parallel lines, of the curving shadows of the trees, the radiating glow of the angel, the curves of the landscape, the hatching shadows on Abraham’s legs, Ugo was carving between those lines. I’m especially tickled by the idea that all the wood depicted here—the sticks of the altar, the trunks of the surrounding trees—was carved into a block of wood, and the curved lines often resemble the striations of tree-rings.

OK, so we have a convincing, stand-alone scene of the most famous, most-often-depicted part of the Abraham-Isaac story. But Ugo da Carpi was also working with a publisher, Bernardino Benalio, and in February 1515, Benalio wrote a privilege (asking for copyright protection) to the Venetian government to be able to print and sell some books and images including “la hystoria del sacrifitio de Abraham.” In the Renaissance, the divisions between the labor of the artist-designer, wood-block carver, and publisher were quite fluid, often overlapping. Ugo da Carpi took Titian’s compositions and themes, added an angel quoted from Dürer, and then, possibly because of a commission from Benalio associated with that privilege, expanded what started as a single sheet print into a larger, more ambitious four-sheet print. In this case, one or more of the three decided it would sell better as a larger scene. Later editions included Titian’s name in that title cartouche (where it says Sacrificio del Patriarca Abraham), no doubt capitalizing on Titian’s growing fame.

This also allowed the print to be more expensive, and to include the “prequel” to the action. Because this part of the story is less well-known, I’ll quote here the scriptures where it is found: And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood for the burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him…. And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you. (Genesis 22: 3, 5)

Detail of Figure 1.

This accounts for the two fellows featured in the lower left quadrant. Abraham strides into the scene, following Isaac, who bends under the weight of the bundled sticks of wood, that to me resemble a bunch of asparagus spears. The two young men seem more than ready to take their time off; one holds the donkey’s reins and doffs his fuzzy hat, standing jauntily in a more contemporary outfit with buttons and a wide collar and calf-high boots. The other lounges on a rock, leaning on his hand and turns towards Abraham. They seem more like spectators of a procession, stand-ins for the audience as we watch Abraham and Isaac continue on with the intended errand, with inscrutable expressions. Do they know, as Isaac does not, the injunction that Abraham kill his son? Or do they know, as Renaissance viewers of this print would have, the reassuring outcome of the angel’s intervention?

In any case, their bodies are my example of significant representation, divided and carried over the edges of the papers. Between the two right papers we find the non-significant representation of the rocky path—even though the path doesn’t clearly lead up, rather goes back as an underpass below the altar— and a somewhat awkward tree stump; but the lounging youth is a great example of showing the printmaker’s skill in dividing significant representation over the break. (They are also an example of the pastoral in the art of Renaissance Venice, to which I will return in Part 2.)

Ugo da Carpi did a good job connecting the lines of the lounging fellow’s collar and wrist, while (as with Mantegna’s sea nymph) just barely pressing his knee to the join on one side and his hair grazing the other. The easy pose seems to belie the difficulty in making the carved woodblocks and the printed paper match believably. Well done, Ugo. But the hat-doffing youth doesn’t fare quite as well. His head is cut right at the crown, and matches only so-so, and his hat doesn’t continue at all (Ugo!? You’re better than this. Though, some impressions printed up better than others, it’s true). But he does hold the donkey’s reins, and in doing so, and being more dressed in modern attire, he and his lounging friend connect to the upper left quadrant in theme.

The join between the upper right and left quadrants is less convincing. The tree continues over (non-significant representation), even though the branches are more white and fluffy, more like clouds in the sky on the left; but the hill slope basically doesn’t continue at all. Neither does the scale of the distant landscape on the upper left match the closer action on the upper right. This emphasizes the “mountain” setting for the almost-sacrifice, but makes the space confusingly close to the lounging youth. The less successful moments at the edges make me think that it was a somewhat rushed job, to expand the original printed composition of the upper right scene to a larger print, to be able to sell a more expensive print more quickly.

So, when you are next looking at an artwork, pay attention to the edges of the composition, to the breaks in the joins, to the areas right next to the frame. You might discover something about the working process, the material considerations, and the decisions the artist made—it might turn out to be fundamental to the viewing experience.

Tune in next week for the end of my discussion of this scene, and how it uses what art historians call continuous narration. I think it’s an appropriate theme, since this post is

….to be continued.

From the King James Version (itself a Renaissance document): Genesis, Ch 22: 1-13. And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said unto him, Abraham: and he said, Behold, here I am. And he said, Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of. And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son, and clave the wood for the burnt offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him. Then on the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw the place afar off. And Abraham said unto his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you. And Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son; and he took the fire in his hand, and a knife; and they went both of them together. And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering? And Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together. And they came to the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built an altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar upon the wood. And Abraham stretched forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his son. And the angel of the Lord called unto him out of heaven, and said, Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here am I. And he said, Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do though any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me. And Abraham lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold behind him a ram caught in the thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering in the stead of his son.