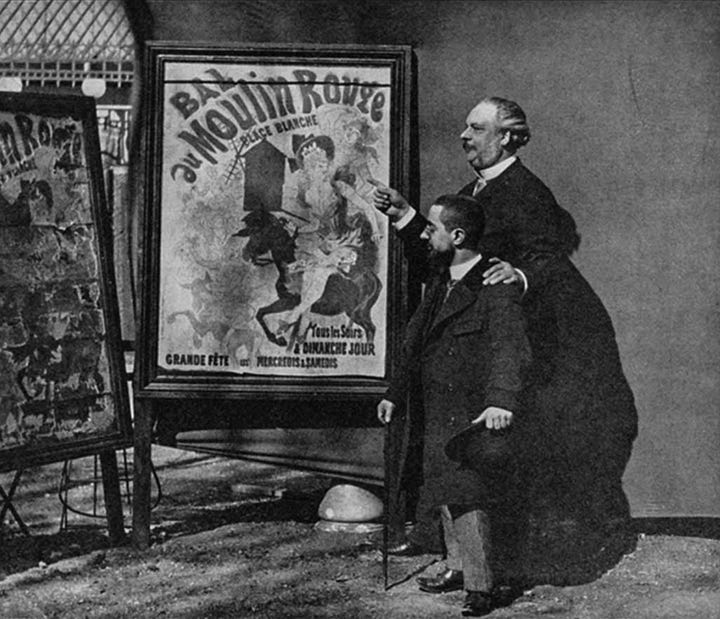

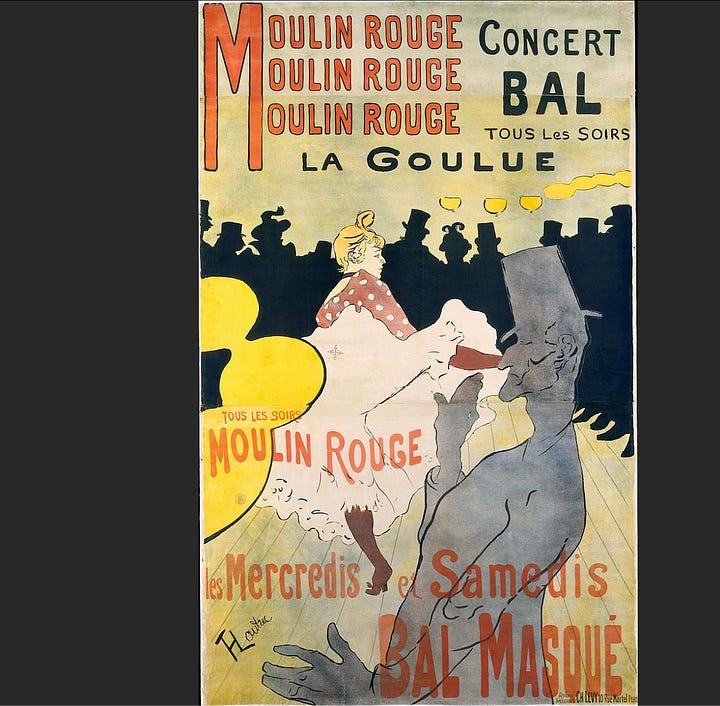

The painting that hung over the bar at the Moulin Rouge, by Toulouse-Lautrec

That detail of the dancer's loopy bun! Not to mention her red stockings. And goodbye, have a nice evening, Mr. Stripeypants.

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance (1889-90). Oil on Canvas, 45 1/2 × 59 inches (115.6 × 149.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art

Today’s painting can be jarring to the eyes at first. It’s pretty big, but not pretty, with clash-y unappealing colors of olive brown, dull green, and pink-plus-red; the crowd of unhandsome people in steep perspective; the unfinished, sketchy quality of the paint. (It helps to brighten your screen, otherwise it looks even more dull than irl.) At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance only becomes more riveting and interesting after a longer look, and then you see the way the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was able to quickly activate the space, gather quirky personalities, and capture the energy of the early heady days of the Moulin Rouge nightclub.

I went to college not far from Philadelphia, and could take the regional train to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for my art history assignments. At the Moulin Rouge was one of the possibilities for a close looking assignment in my 19th Century Art class. I had never heard of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec before looking at this painting, and hadn’t given him much thought since, but I’ve been doing research about him lately and am more and more impressed with his artistry. Toulouse-Lautrec has got to be one of the more underappreciated artists of the late 19th century, overshadowed in public awareness by Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Monet and van Gogh. But like them, and like his contemporary (whom he greatly admired) Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec depicted scenes of Modern life, admired Japanese prints, and was an active participant in the nightlife and “modern life” of Paris.

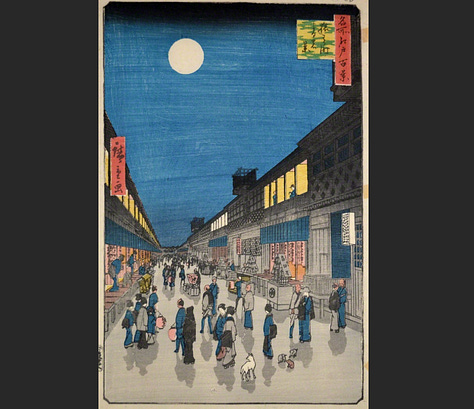

At the Moulin Rouge was painted right when the nightclub was the new popular “it place” in Paris, newly and still famous for the cancan, a dance step with high kicks that show off the dancers’ legs. It was in a rougher part of town near the artsy Montmartre neighborhood, but where upper middle class men could meet their friends and go to ogle the cancan dancers’ underskirts.

The painting depicts an interior hall in the Moulin Rouge, a big space with a bar in the back where men and a few women gather in conversational groups, and in front a fancy woman arrives with her companion (read: chaperone). In the middle ground, two dancers make use of the open floor space to practice exuberant dance steps; the dancing woman’s movement is the most riveting detail of this painting. A woman in a dun-colored dress flares up on her right toe, kicking out her left leg and opening both arms to lift her skirts, showing off her white petticoat and her well-formed calves in red stockings. You might think this would be an "ooh la la!” moment, but her dancing is less for titillation and more for the way her body defines the space in the painting, and for her vibrant, idiosyncratic energy. Toulouse-Lautrec painted her petticoat with quick sketchy brushstrokes to mimic and underscore its movement and swishiness as she dances.

This woman is practicing new dance steps; facing her is a skinny man with wobbly, wavy legs. This character was a fellow named Valentin, a performer whose nickname was “the Boneless" because of his flexibility. (Toulouse-Lautrec identified him with a note on the back of the canvas.) He kicks out his right leg and holds his arms akimbo. But he doesn’t take up as much space as the female dancer in front of him, and his top hat and darker olive-black suit make him blend in more with the other men in the room.

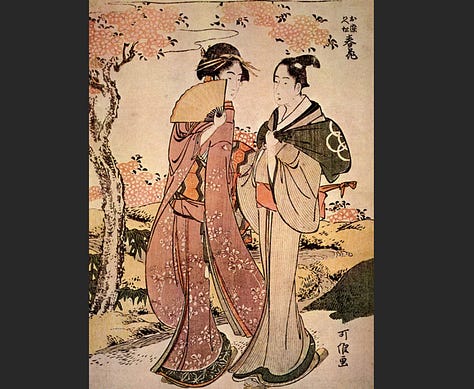

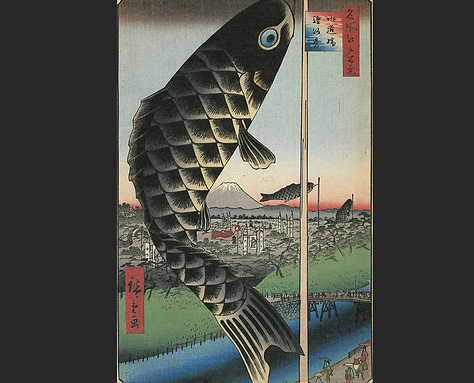

Both dancers—and really, all the people here—have strong outlines that define their places in the room. Rather than using modeling or shading to depict three-dimensionality, Toulouse-Lautrec paints swelling outlines and defined but flat shapes of color. He learned this from studying the Japanese prints that were circulating in Paris, and were admired by other artists, from Monet to van Gogh to Mary Cassatt. (Speaking of whom: I am really looking forward to seeing the upcoming exhibit at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco – local friends, let me know in the comments if you want to join me for that exhibition.)

Japanese prints also commonly use the space-creating technique of having larger elements in front and smaller elements in back. Toulouse-Lautrec uses this dramatically in this painting by having the two large women in the foreground, especially the woman in pink. This woman almost shows us her profile, but she turns away from the viewer as she walks in her hands demurely clasping her handbag. Her eyes lowered, she knows she is dressed in the latest fashion, with a bustled skirt, fluffy boa, and a hat mounded with feathers.

She is going to this nightclub to be seen, but with a chaperone—who not only serves to give her propriety but also heightens her elegance through contrast, by being more dowdily dressed in an olive green that blends into the background. Toulouse-Lautrec rendered her in silhouette with a flatter hat and a lower bun, pert lips and a weak ear, signifying that she is not as fashionable as her self-consciously pretty companion. Although this heightens my curiosity— since we can barely see her face behind the pink lady’s big hat, who are we to say?

The pink and red of the fancy lady’s dress clashes with the olive greens, browns and hazy blacks of the rest of the painting, besides a few pops of red. The uncomfortable colors underscore the interior unnatural lighting of the oil lamps in the back near the posts or pilasters. Toulouse-Lautrec is known for this unnatural color, a way to try to capture the carnivalesque feel of the nightlife.* I mean this not like it’s a colorful carnival, but the way that people can be loosened from their expected social classes and rules at the Moulin Rouge nightclub.

Toulouse Lautrec’s interest lies in the variety of types of people who otherwise wouldn’t mingle; he makes each person idiosyncratic no matter what their class background. Some are less “finished" than others, as though Toulouse-Lautrec has, with a minimum of line, captured their personality and then moves on to the next, a sort of hurriedness and burst of activity to capture the active scene enacted in his painting. Look at some of the faces we see; some have a weirdness about them. What’s with Mr. Blueface, or Mr. Skull, or the triangular chin of Valentin?

The unfinished quality gives them idiosyncrasies and animation. It makes us want to enter into their conversations, go eavesdrop on the man and his wife—or mistress, since this was a gathering outside the normal respectable places for the middle class.

The multitude of persons continues beyond the edge of the painting, underscored by the man (Mr. Stripeypants) on the left who strolls out of the painting, his nose cut off by the edge, his hands in his pockets. He may be accompanied by a companion with him that looks like it was originally a pentimento (which means a place where the artist visibly changed his mind, or “repented”); you can see the ghost of a top hat, a different type of cloak, next to Stripey.

To return to the female dancer, she really makes this painting. The activity spirals out from around her as she hops backwards and to the side in her ankle boots, making space and pushing away the other people with her big gestures. We can’t really see her face, but her hair is bound in a loopy bun, which we can almost see bounce along with her vigorous dance.

Her movement is in stark contrast to the men in their top hats just standing around and gossiping. The multiple lights have cast shadows both in front of and behind her on the floorboards, as well as those of the “boneless” Valentin. She’s vigorous and gutsy, intent on getting the dance step right; she doesn’t care that her petticoats and red stockings are showing. She’s more interested in getting that dance right than being exhibitionist. In this she’s so different from the lady in pink, there to be seen— we cannot imagine Mam’sell Pinkdress suddenly busting a move.

This painting must’ve represented its various clientele in a way that flattered them enough, as it was displayed above the bar at the Moulin Rouge for its first few years of existence. Toulouse-Lautrec was often among the guests there and knew the manager. He made posters advertising the nightclub’s events, and his expertise at making space through line and blocks of color was perfect for the poster medium.

Toulouse-Lautrec wasn’t obligated to hang out at the nightclub in a slightly seedy part of town, with artists, prostitutes, and dancers. He was a wealthy aristocrat from the provinces. He had family money and enjoyed hosting his friends, eating well, and (above all, unfortunately for his health) drinking a lot. He suffered from stunted growth from childhood injuries and possibly from the congenital inbreeding of his aristocratic family; this may have contributed to his feeling less at ease in upper class circles and more at home with social outcasts. He made an extremely moving series of paintings of prostitutes, whom he depicted with sensitivity and grace. He let neither his aristocratic background nor his handicaps hinder him from his own careful looking at the world around him and his prolific artistic output. He had a knack for depicting his contemporaries with boatloads of personality, sometimes approaching caricature, but with a style I find less to be less about making fun and more about distinguishing personas at a time when conformity in dress was the rule.

At the Moulin-Rouge: The Dance, Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting may have its ugly, clashing colors, but nevertheless provides so much interest in personality and action at a particular contemporary moment in this new nightclub in 1890’s Paris. He is one of the artists who I keep appreciating more the more I learn and look. Part of the reason he is not better known or appreciated today as that he died quite young, alcoholism contributing to his early death at only age 36—another one of those talents who died too young. (As the Tom Lehrer joke about Mozart goes, by the time Toulouse-Lautrec was my age, he had been dead for 10 years!)

*See for example Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge (1892-95), Oil on Canvas, Art Institute of Chicago—it’s a more famous painting especially for the garish underlighting that turns a woman’s face green and white. We’ll save that for another day.

This post is dedicated to my excellent art history professor at Swarthmore College, Constance Cain Hungerford, who also died too early in her 70s. She gave riveting, easy-to-take-notes lectures; taught me the value of committing dates and long titles to memory (The Dynamic Hieroglyphics of the Bal Tabarin was on one midterm exam (below—I’d love to write about this one soon); challenged me in my first art history seminar; and wrote me letters of recommendation. She did me the favor of telling me (rightly, at the time) that I wouldn’t get accepted into Yale, which only spurred me to work harder and I was later accepted, after I had earned my masters from Brown. At the Moulin Rouge was the subject of my first paper for her, wherein I first used the phrase (which she liked:) “loopy bun.”

Gino Severini, Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, 1912. Oil on Canvas with Sequins, 63 5/8 x 61 1/2" (161.6 x 156.2 cm). Museum of Modern Art, NY

A rich description of a vivid work! Thanks for making the connection to Japonisme—fascinating stuff.

I’m convinced from this that Toulouse-Lautrec was a painter of modern life in Baudelaire’s sense, the voyeur who extracts something heroic from the banal.

“…. this man, such as I have depicted him—this solitary, gifted with an active imagination, ceaselessly journeying across the great human desert—has an aim loftier than that of a mere flaneur, an aim more general, something other than the fugitive pleasure of circumstance. He is looking for that quality which you must allow me to call `modernity'; for I know of no better word to express the idea I have in mind. He makes it his business to extract from fashion whatever element it may contain of poetry within history, to distill the eternal from the transitory.

“By ‘modernity’ I mean the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable.” (“Le Peintre de la vie moderne,” 1863)