Inventive Illustrations after Petrarch's Triumph of Love

Look out for Cupid's pungent arrows! Pair with a listen to Billie Holiday's recording of "I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm."

To counter the chill of February, I’m bringing you for the first time a four-part series: artworks from Renaissance Italy on the theme of the Triumph of Love. Of course love is a perennial theme around Valentine’s day, with its roses and cards and overbooked restaurants; or mild panic about how to fete your sweetheart or make sure your kid has a card not leaving out anyone in their class! But my focus here will be on a specific, visualized love-theme particularly popular in quattrocento (1400-1500, or fifteenth century) Italy.

The Triumph of Love theme, showing Cupid as the honoree on a parade float, combined courtly love from the literature and songs of the late Medieval with the rediscovery of the triumphal procession from ancient Rome. This theme comes from a long poem called The Triumphs (i Trionfi) written by Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), or as we English speakers traditionally call him, Petrarch, the father of the Petrarchan sonnet (usually about love for an idealized woman) and one of the earliest scholars obsessed with classical authors such as Cicero. The Triumphs inspired hundreds, perhaps thousands, of artworks and everyone in Italy would have been familiar with this work or at least its themes. Its fame might be comparable to, say, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, or Taylor Swift, or the Super Bowl, or Taylor Swift at the Super Bowl. Very Of-the-Moment, Very Famous.

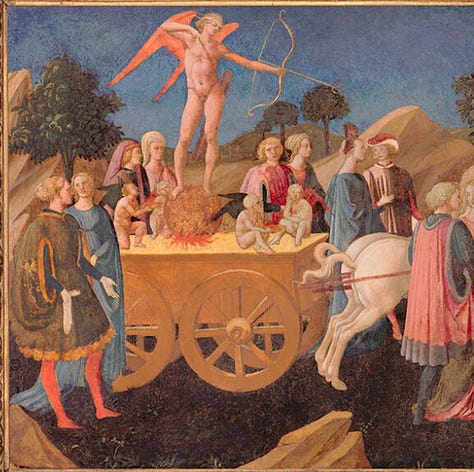

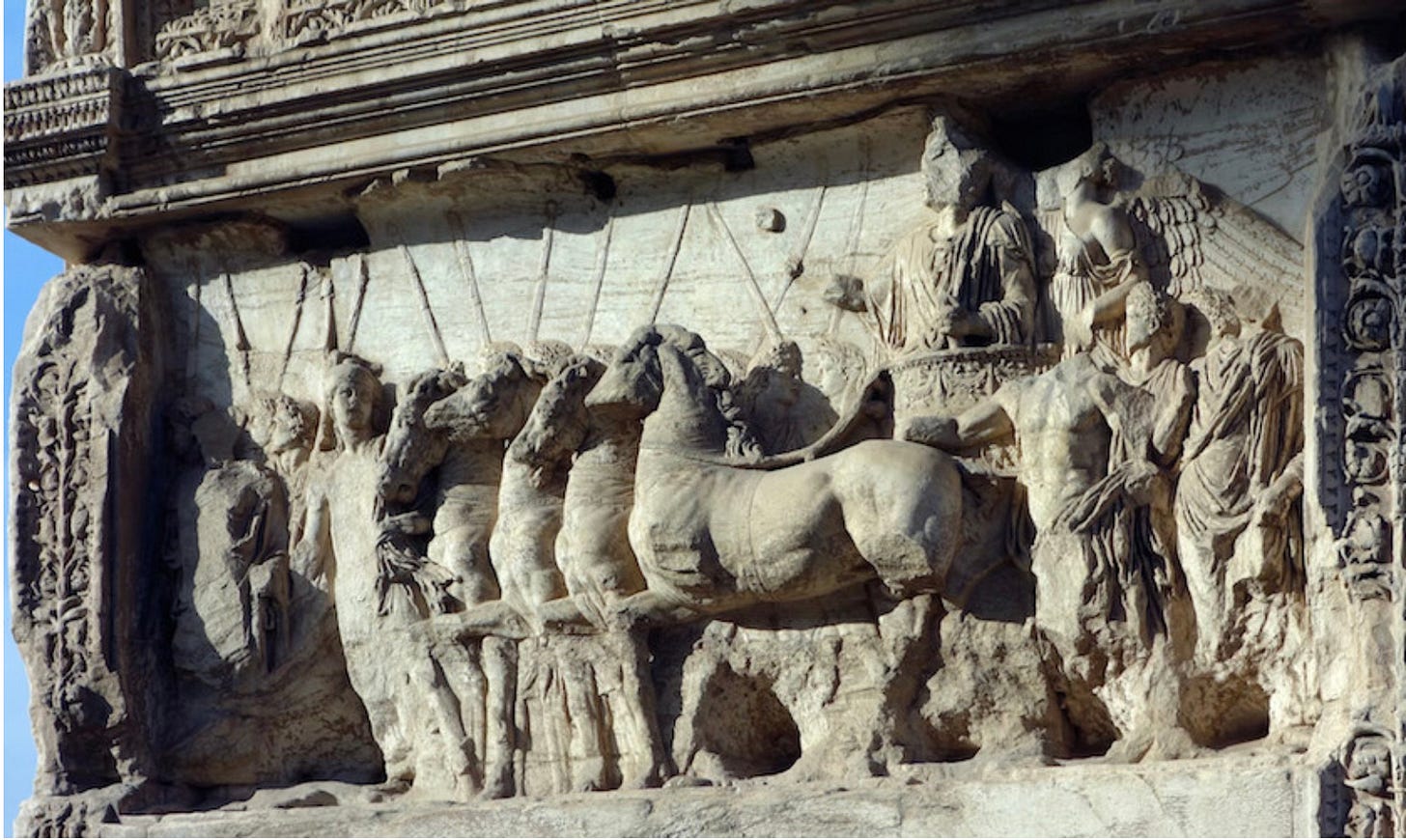

Petrarch’s Triumphs are an extended, rhymed meditation on what are the forces that have the most conquering power, and he begins with the Triumph of Love. The cliche today may be that love is the motivating force that makes the world go round (though current events have me pessimistic about that), but for Petrarch, it was about how Love can bring about the downfall of mighty generals, fighters, and even gods—Jupiter himself is one major victim of Love’s arrows—and he lists many famous and powerful men who have been defeated by their love for women. His narrator describes a vision with a fiery chariot drawn by four horses, whiter than snow, carrying a youth with thousand-colored wings completely naked except for the quiver of arrows and bow he holds—winged Cupid, in all but name. I’ve included the relevant passage below in Italian and English. It’s clear that Petrarch has a Roman triumphal procession in mind, as he directly compares this visionary chariot to the ones that brought triumphant conquerors gloriously into Rome—specifically naming the Campidoglio, a hill in Rome that is now the site of a famous piazza designed by Michelangelo. Roman imagery of the triumphal procession, as on the reliefs of the Arch of Titus, included horses drawing the chariot and a winged figure who would ride behind the triumphator to remind him not to let this pomp and adulation go to his head, whispering “remember, you are still mortal.”

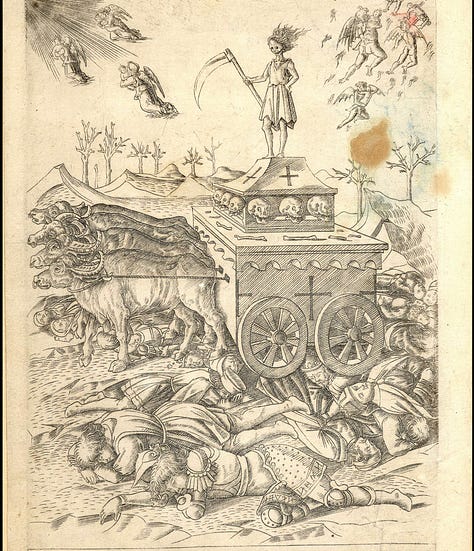

Love here, though, is immortal and invincible, not even needing any protective armor, naked and standing on a Chariot of Fire, because Love is hottt. Petrarch’s narrator describes innumerable mortals around the chariot, some taken in battle (again like Roman triumphs, bringing captives into the procession), some wounded, and some dead. You may rightly wonder how Petrarch could imagine dead people keeping up with the parade—but actually we’re outside of time and they died by or for love when they were mortal—but later illustrators included the dead sometimes by having the chariot’s wheels rolling over their unfortunate bodies. The litany of captives included mythological, biblical, and literary figures, whom love has famously wounded and defeated. And the very first person named? Julius Caesar, who later in the Renaissance would be the absolute archetype of the Roman triumphant emperor. Including Roman emperors PLUS biblical characters, AND having them be susceptible to the agonies of courtly love?! This checks a lot of boxes for an early Renaissance audience.

Petrarch’s poem includes enough imagery to give artists something to go on: a fiery chariot, a naked archer with rainbow wings, four splendid white horses, a bunch of people. Jupiter, bound and riding on the chariot. But he doesn’t describe the later triumphs—and there are six triumphs in all! Kind of like the rock, paper, scissors game, each successive theme conquers the previous one. Love is bound and captive by by Chastity in the second triumph (an appropriate symbol for Galentine’s Day, perhaps?), Chastity is defeated by Death, Death by Fame, Fame by Time, and finally, Time by Eternity. Eternity is understood, and certainly depicted, as divinity (sometimes as the Trinity) giving the final triumph a Christianizing turn. And if God is Love, whelp, we’re back to the beginning! But divine love is implied to be on a holier plane than the carnal Love (read: for women) inflicted by Cupid’s “pungent arrows” in the first Triumph.

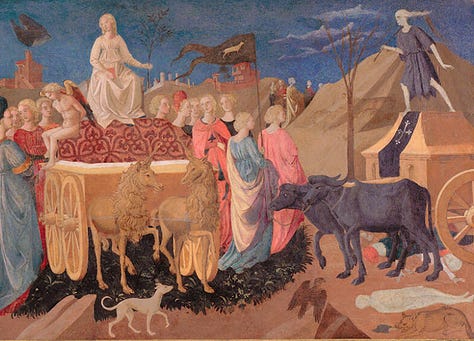

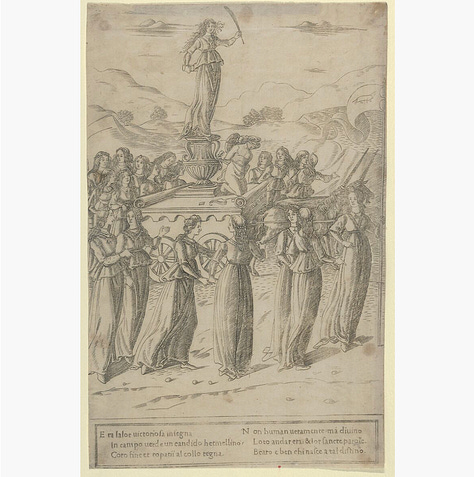

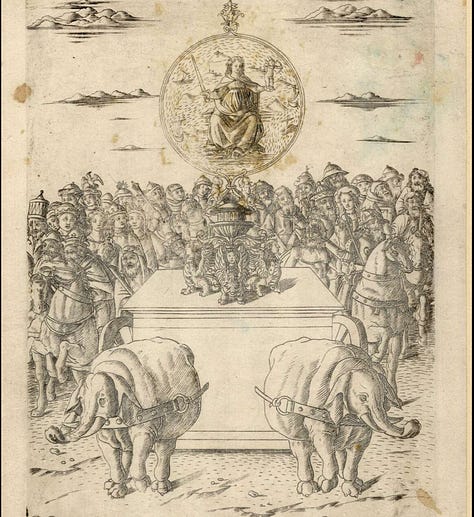

In order to illustrate the successive Triumphs, manuscript painters and illustrators for book editions adapted the Triumph of Love imagery with variations on the theme. They put an allegorical figure representing that theme on a chariot or carriage, pulled by symbolic animals, and surrounded the chariot with an entourage of participants associated with the main triumphal figure. I don’t know who came up with the earliest variations, but the imagery spread first through manuscripts illustrating the Triumphs and then in printed books, with dozens of editions published. These works played a major role in the popularizing and codifying of triumph imagery for later artworks.

Chastity’s chariot is pulled by unicorns, a mythological animal associated with purity and only able to be captured by a virgin. Death is pulled by oxen or buffalo (since they pull hearses? I’ll have to review the imagery after the Black Death plagues of the 14th century, which featured Triumphs of Death rolling over bodies); Fame by elephants, another possible reference to Roman triumphs; Time by Stags with enormous antlers, and Eternity generally by the symbols of the four Evangelists: an Angel or winged man, an Ox, an Eagle, and a Lion. These became the standard choices, although sometimes illustrators reached for even more fantastical creatures such as dragons and serpents for Death.

This triumphal imagery would be copied again and again, and modified and adapted for at least the next two hundred years. See if your local art museum—or rare books library—has examples inspired by Petrarch’s Triumphs! Let me know in the comments!

Here are the excerpts from Petrarch’s Triumph of Love referenced above—the translations above are mine but the excerpt and translation below is from Peter Sadlon’s website which has oodles more information about Petrarch.

Springtime and love and scorn and tearfulness

Again had brought me to that Vale Enclosed

Where from my heart its heavy burdens fall;

And there, amid the grasses, faint from weeping,

0'ercome with sleep, I saw a spacious light

Wherein were ample grief and little joy.

A leader, conquering and supreme, I saw,

Such as triumphal chariots used to bear

To glorious honour on the Capitol.

Never had I beheld a sight like this --

Thanks to the sorry age in which I live,

Bereft of valor, and o'erfilled with pride --

And I, desirous evermore to learn,

Lifted my weary eyes, and gazed upon

This scene, so wondrous and so beautiful

Four steeds I saw, whiter than whitest snow,

And on a fiery car a cruel youth

With bow in hand and arrows at his side.

No fear had he, nor armor wore, nor shield,

But on his shoulders he had two great wings Of

a thousand hues; his body was all bare.

And round about were mortals beyond count:

Some of them were but captives, some were slain,

And some were wounded by his pungent arrows.

…Amor, gli sdegni, e 'l pianto, e la stagione

ricondotto m'aveano al chiuso loco

ov'ogni fascio il cor lasso ripone.

Ivi fra l'erbe, già del pianger fioco,

vinto dal sonno, vidi una gran luce,

e dentro, assai dolor con breve gioco,

vidi un vittorïoso e sommo duce

pur com'un di color che 'n Campidoglio

triunfal carro a gran gloria conduce.

I' che gioir di tal vista non soglio

per lo secol noioso in ch'i' mi trovo,

voto d'ogni valor, pien d'ogni orgoglio,

l'abito in vista sì leggiadro e novo

mirai, alzando gli occhi gravi e stanchi,

ch'altro diletto che 'mparar non provo:

quattro destrier vie più che neve bianchi;

sovr'un carro di foco un garzon crudo

con arco in man e con saette a' fianchi;

nulla temea, però non maglia o scudo,

ma sugli omeri avea sol due grand'ali

di color mille, tutto l'altro ignudo;

d'intorno innumerabili mortali,

parte presi in battaglia e parte occisi,

parte feriti di pungenti strali.