Pudgy Baby Humor in Titian's Ca'Pesaro Altarpiece

Plus moments of typology and drama in a sacra conversazione. To wear: a tablecloth's worth of expensive velvet.

When I was in Venice doing research for my dissertation, I briefly lived in the neighborhood around the basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, passing by this enormous church every day and going inside often. It’s amazing to see Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin, painted in honor of the dedicatee of the church, triple-framed by the Renaissance architectural structure; the apse with its windows surrounding the painting with light; and—in what is actually the first framing—the way the painting fits into the choir opening (in the rood screen) as you approach after entering the main door of the church. Though a fully Renaissance work, the Assumption fits beautifully in the already existing mostly Gothic architecture of the church.

Perhaps the Friars gave Titian that commission after seeing the dynamism and color of his earlier works such as the Magnani-Rocca Madonna (see my post of a couple weeks ago)—and he was just getting started. Just a few years later, he completed an even more innovative sacra conversazione altarpiece for the Pesaro family altar on the left side aisle of the same basilica. In his Ca’ Pesaro Altarpiece (produced from 1519 to 1526. so called because it was for the “House of Pesaro”— Casa Pesaro, but shortened in Venetian dialect to Ca’) Titian amped up the asymmetry and interactions of the M-R Madonna, relating the composition directly to its placement in the Frari.

The painting remains where it was originally intended on the left wall in another architecturally Renaissance frame. Obviously, after finishing the Assumption, Titian was already very familiar with the church layout and the location of the Pesaro altar. Many people have noted that Titian kept this location in mind when he took the traditional symmetrical composition of sacre conversazioni, with Madonna and Child in the middle, and saints and donors flanking her throne, and twisted it diagonally off-center. This serves to welcome the actual visitor walking up this aisle, as though we, too, are approaching the Virgin from the same direction and could walk up into the painting towards her.

I would add that the Ca’ Pesaro Altarpiece is even more revolutionary in that Titian included, within the dynamic interactions between the characters, narrative moments across different historical and theological times; and more whimsically, it is a good example of Titian’s gently ribald but unmistakable humor.

But first, who are these characters?

Most importantly, the Virgin Mary sits high up on an invisible throne, supporting the baby Christ as he stands on her lap. How did she get up there? It looks like there is no easy earthly way up or down—maybe it is behind the platform, allowing for theatrical entrances—but also she’s capable of miracles so this question is beside the point. This curious pedestal-box also renders the interceding saints nearby theologically necessary in a metaphorical way—through them, the patrons and worshippers can reach her. She looks down at St Peter, who leans towards his open book and turns his gaze towards the kneeling donor. The deep green, gold, and blue fabrics around him remind us of Titian’s talent with color. We can tell this is Saint Peter because he’s a bearded man with an elaborate, hefty key, his attribute, leaning on the step towards him, just below. Otherwise a big key on a marble staircase doesn’t make much sense.

A compositional cascade effect falls from Mary to Peter to Jacopo Pesaro. Peter's body turns and leans toward his book and the Virgin, his head looks back to JP, reminding us of the way bodies turned one way and gazed the other in the Magnani Rocca Madonna of my previous post.

Jacopo Pesaro was a commander in the papal navy, who won a decisive battle against the Ottoman Empire in 1502. Remember (from my post on Ottoman Iznik tile) the Ottoman Empire was a feared, worthy opponent, at the height of its power, so winning a battle against them would have seemed to require divine intervention. Jacopo Pesaro may have felt that their forces only conquered through the help of the Virgin, and it is quite possible that this altarpiece was partly the result of a mid-battle prayer or vow, or ex-voto (Latin for “from a vow”); that is, if the Virgin would help him win, he would commission an altarpiece commemorating that win for his family altar. (I say partly because he had already commissioned an ex-voto from Titian, of himself being presented to Saint Peter, who may have been his particular favorite saint or maybe just because Peter was the first pope.) Here he kneels in very expensive black robes, his gloved hands pressed together in worship and holding a rolled document (maybe); his eyes are raised to meet Mary’s downward gaze, which is just ambiguous enough to include those of us who are also approaching her by walking up the nave of the Frari.

Behind JP stands a Christian knight—this could be Saint George, since his attributes are a suit of armor and often a flag, or just an allegorical figure of Christian knighthood— hoisting the giant flag with the heraldic arms of the pope and of the Pesaro family (smaller one, obviously). The knight leads two captives, an Ottoman captive distinguishable by his turban, and another one behind him, darker, in shadow and more difficult to see. The knight strides confidently into the scene, but the heavy flag drapes itself in a casually familiar way over his shoulder and behind his head, and he turns to his captives as though they are having a conversation as equals, or at least a general feeling of current peace and mutual respect. The Ottoman man leans in as though to hear the back story of the present company, like when you walk into a party with a friend, given by your friend’s friends who you haven’t met yet.

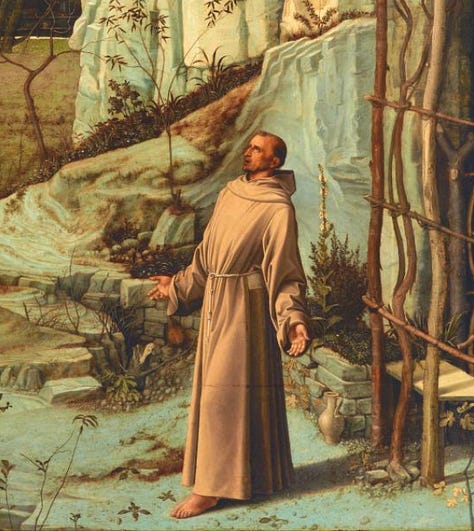

On the other side of Mary, Saint Francis stands looking up at her in his Franciscan robes, accompanied by St Anthony, his Paduan sidekick, also a Franciscan. Their double presence makes sense in a Franciscan church. Like St. Peter, Francis directs the viewer’s focus in two directions: up, with an intent gaze at the baby Christ, and down, by opening his hands as though he was a protective umbrella over other members of the Pesaro family (only male ones, for some reason, in this instance). Imagining his arms forming a canopy like a cloak of shelter above them is not such a stretch in Venice, and in this church: it mimics the way the Madonna della Misericordia’s cloak opens to protect the worshiping people underneath. This website has conveniently collected all the Madonna della Misericordia paintings, and sculptures over doorways and on buildings throughout Venice, open to the streets for all passersby to see. It also includes examples from this Frari church, from a painting predating Titian’s Assumption—so he knew about this tradition, unquestionably.

Actually, St. Francis’ spread-arm pose does triple duty, for not only does it protect and present the Pesaro fellas, it also functions as both his attribute AND as Titian’s insertion of a narrative moment in the sacra conversazione. To explain a bit further: Francis’ open hands show us his received stigmata, or a divinely rendered simulacrum of the marks of Christ’s wounds from the nailing of his hands to the cross, one of the attributes identifying St. Francis. At the same time, Francis’ stance with palms open imitates the moment when he was receiving that stigmata, in a miniature reenactment of that visionary moment. There are many paintings that show Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (feel free to google-image this), but they all show his hands open, out or up during a vision. Often the vision is of a crucified Christ-seraphim directing laser lines to his palms, but sometimes it shows a quieter, more contemplative moment. Titian here seems to quote most particularly the St. Francis by Giovanni Bellini, which some have seen as his reception of the stigmata through sunlight. (Bellini’s St Francis is in the Frick Gallery, newly open after a renovation and I encourage everyone in the NY vicinity to go and tell me about your visit).

By referring to this pivotal event in St Francis’ life, Titian includes a narrative moment in what had been ostensibly a timeless, static, sacra conversazione, beyond time and certainly after the included saints’ deaths. Not only is this revolutionary to my mind, it also adds a heightened level of typological poignancy: Francis is gazing up at the baby Christ, knowing that that baby would grow up to be crucified and then give the marks of his sacrificial death to Francis centuries later.

While Saint Francis is all seriousness, understandably, baby Christ is playfully lifting his Mother’s veil above his head—it might have been over his face just a moment before. He is playing peekaboo, the delight of nine-month-olds the world over! Object permanence! So fun! His next move will be to pull the white cloth over his face again. And Mr. Serious Saint Francis is patient but having none of it. Chubby baby Christ balances a bit precariously, standing on one leg and kicking out his other foot, beginning to walk out towards us, the viewer (see my post on Mary Cassatt’s retitled-by-me Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine); but his multi-tasking mother’s gentle, long-fingered hands remain ready to stabilize him. This contrast between peekaboo Christ and St. Francis is the first moment of Titian’s observational humor coming through.

I also see Titian’s humor in the pair of winged putti above, other chubby toddler angels with scrumptious triple-thighs. They struggle with the cross to keep it upright, but they only have clouds as their base. (What could go wrong?!) This results in one baby turning his backside to us, mooning the viewer, a moment of possible irreverence—but understandable and cute rather than sacrilegious. The babies, angels above and Christ below, ignore the solemnity of the adults in the scene in their playfulness, enlivening the painting for us, the viewers.

Perhaps similarly, the youngest Pesaro boy looks out to make eye contact with us, as a choric figure to bring our attention into the painting. Maybe he is also distracted by our presence, like a well-meaning but fidgety older child in church. Mostly obscured by the vast amount of the ostentatiously expensive pyramid of double-pile dark-pink velvet* of his (maybe) father, this youngster turns his gaze to us. This time we viewers are the objects impermanent, passing through the church of the Frari, and the Pesaro boy, his relatives, the saints, and the painting, are still where Titian painted for them to be, 500 years ago.

*Contemporary audiences would have visually calculated how expensive this and other fabrics painted here would have been, an indication of the very large amount of wealth in the Pesaro family. I would guess it would have been more expensive than the whole painting.