Musical Competition meets Renaissance Rivalry in Giulio Sanuto's Apollo and Marsyas

A concert where the stakes are extremely high, higher even than the notes. Clothes optional. Enjoy with lira da braccio and shawm music (included at the end)!

I chose this print to coincide with an exhibition going on in London right now, so that those interested in Renaissance art could be sure to know about it! My dear readers across the pond, if I were a stone’s throw from London I would head over to an exhibition at the Royal Academy, called Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael: Florence, 1504. All household names now, the three greats of the High Renaissance were in different stages of their career when they converged in Florence that year. Leonardo (Leonardo da Vinci, but just say “Leonardo”) was the older esteemed artist, Michelangelo was quite a bit younger but definitely another artist in high demand, and Raphael was precociously talented but basically still a student, eagerly learning from the other two. In 1504 the city of Florence commissioned Leonardo and Michelangelo to paint giant frescoes for the city hall, featuring glorious battles to glorify Florence’s glorious history.* Both artists used the opportunity to generate new creative ideas over simple civic pride and propaganda. Leonardo depicted a vigorous moment of armed horsemen colliding during the Battle of Anghiari, and Michelangelo prepared studies and a cartoon (a full-scale working drawing) depicting men taking a swim in a river just at the moment they were called to fight in the Battle of Cascina, so they had to quickly jump out of the water to prepare. This gave Michelangelo the excuse to fill his composition with studies of nude men in an enormous variety of postures.

Can you imagine the excitement of having these two masters working out frescos for walls directly across from each other, in the same room, at the same time? The Royal Academy exhibition asks this question and shows the planned scale of the frescos, and various ways Leonardo and Michelangelo affected each other’s artistry. I invite you to read this excellent review of that exhibition happening in London, to gain more background on that moment, by my fellow Substack art historian Rebecca Marks.

While neither Michelangelo nor Leonardo finished the battle frescos, drawings for both scenes lasted long enough to be copied and studied and shared by every major artist coming through Florence. Divided up and handed round, the studies and cartoons (especially Michelangelo’s cartoon for the Battle of Cascina) were called “the school of the world“ by the later artist and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini because they were copied by so many. Countless painters and printmakers copied the male nude poses invented by Michelangelo, and the fantastic horses, costumes, expressions and general energy of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari; both projects inspired many 16th century artworks, maybe especially prints.

One of these prints is our topic today, an ambitious, large, three-sheet print by Giulio Sanuto that references Leonardo, Michelangelo, AND Raphael. Unless you are familiar with this artistic context, and the narrative depicted, you might have no idea what’s going on. Maybe it’s an ancient Greek party scene? (No, but that’s not a bad guess, thanks, Mom!) What is going on with these nude musicians lounging around? In order to make sense of this image, let me first tell you the story depicted. In the print the story goes from right to left.

THE MYTH OF APOLLO AND MARSYAS

Quite well-known in the Renaissance, the story of Apollo and Marsyas is one of many from classical mythology that warn humans of the dangers of hubris, with the penalties that await for those who try to surpass the gods.** Marsyas was a musician satyr who felt he was the best musician around. He challenged Apollo, the god of reason and music (as well as the sun, but that’s not so relevant here) to a competition to determine who was the better musician. Satyrs, as you know from my post of August 30, were not known for their powers of reason, otherwise he may have thought better of this idea. But Marsyas was determined, and for the competition they invited both a royal mortal, King Midas, and the goddess of wisdom, Minerva, to be the judges. In the story, Apollo plays a lyre and Marsyas pan pipes. One version of the myth says that Apollo started to sing as he played, and Marsyas complained that he was breaking the rules and they were only meant to compete on their various instruments. Apollo retorted that he was using his breath to create music, as Marsyas was blowing on his instrument, so it was practically the same thing. Whatever your opinion about those rules, any challenge against an immortal god was bound to fail, and Minerva called it in Apollo’s favor. The punishment for Marsyas: Apollo would flay him alive.

King Midas could not read the room and protested that Marsyas was actually a pretty good musician—and as a punishment for his foolish judgement in favoring a mortal over Apollo, the two gods gave him donkey’s ears. Midas began to wear a hat everywhere so that no one would know of his shameful new donkey ears, unseemly especially for a king. He managed to keep it a secret from everyone except his barber—obviously you have to take off your hat if you want a haircut—who swore not to tell anyone. The barber did his very best to keep it to himself, but feeling that he would absolutely explode if he didn’t tell it somewhere, he went to a local river and whispered it into the water. But the water carried the secret to the reeds of the riverbank, where the wind picked it up and wafted “King Midas has ass’s ears” throughout the kingdom. There’s a satisfying symmetry in the story that his punishment was carried out by the reeds, like the panpipes or reed instrument Marsyas played, and the wind, who sang it out like music across the land.

GIULIO SANUTO’S PRINT

The engraver, Giulio Sanuto made this story into a monumental work, a print over three large sheets of paper stretching about a meter and a half long and nearly half a meter tall. He used it as a showpiece to demonstrate his skill as an engraver but also to show his erudition: he was well traveled, knew this complex myth, and could quote the greatest artists around.

The earliest part of the story occupies the right hand sheet, showing the competition between Apollo and Marsyas, while Minerva and King Midas sit listening intently to the music. Even though this is an ancient story, both Apollo and Marsyas play Renaissance instruments: Apollo plays a lira da braccio, a bowed string instrument and ancestor of the violin, and Marsyas a reed instrument called a shawm, sort of an early oboe. Apollo turns his back to the viewer and tilts his head dramatically as he plays, showing off his profile and Alexandrian hair. Marsyas tips his shawm up to the sky as if he is draining the last drops of a drink. I cannot imagine that this would be an effective way to produce a beautiful sound, since the kink in the neck would disrupt the airflow, but if I have any wind instrument player readers, please comment if this would even be possible. He doesn’t even center the reed on his lips. Points for enthusiasm, though, Marsyas! Also this gives Giulio Sanuto an excuse to show off his ability to engrave the male nude from both a back and front. As a violinist, I can say with authority that Apollo’s hand position and bow grip are…not terrible (far be it from me to incur divine punishment) so much as prioritizing an explicit quotation from a famous statue you might already know: Michelangelo’s David. The unusual poses of both Apollo and Marsyas, with their twists and jutting knees and elbows recall the nudes in the Battle of Cascina.

Both musicians seem to be actively playing, at the same time, which can’t have been easy on the judges’ discernment! Minerva and King Midas sit as spectators on the left, Minerva leaning in with a head cocked in concentration while Midas leans back with his eyes bugging out and mouth open, either in amazement or stupefaction. Maybe it’s just really loud in such close proximity to the shawm, which can produce quite a piercing sound. I’ll include links to some excellent musicians playing reproductions of both instruments, the Renaissance lira da braccio and the shawm, at the end of this post. Giulio Sanuto puts Midas’ full nude torso on display, too, but you’ll notice he is…less practiced in representing the nude female torso, disappointingly. (Many would say that about Michelangelo, too, actually.) Certainly the emphasis here is on the study of the male nude in variety, the way it was in the Battle of Cascina.

The center sheet shows Apollo again, in an instance of continuous narration (see my post dated November 8 for a definition and examples) bending to pin Marsyas to a rock and brandishing a knife in the middle of the ghastly punishment. You might ask, how can you know they are the same characters—they are not wearing any clothing! But they do have the same hairstyles, and they are pictured with their instrument-attributes. Marsyas’ shawm with its trumpet-like bell lies between him and the rock, and Apollo’s lira da braccio is propped upside down on the rock behind him. This should be in no way a justification for how to treat your instruments, kids. Please put them in a case before you put them on the ground or on rocks. At least Apollo has placed a folded cloak underneath his!

We can see that the gruesome work of flaying has already begun at Marsyas’ legs, for his thighs have the skin peeled back revealing the muscle underneath. We wonder at Marsyas’ ability to withstand this pain, and he does seem to be protesting enough to be pinned down by Apollo‘s full weight on his right bicep. It’s such an unusual twist that Apollo, the god of mental reason, would issue a cruel, corporeal, gory punishment so cooly. If you have any ideas about why, let me know in the comments! I can conjecture that in the 16th century, it could be Sanuto alluding to the study of the (male) body again, as we know Leonardo and Michelangelo made a practice of studying anatomy through human dissection. Let me know if you would like to know more about that.

In the back, we see nine women in classical drapery, several with their own musical instruments, all gathered as though preparing for a group photo around two trees on a hill. This is another quote, this time from Raphael, of the nine muses on Parnassus, a fresco he was working on in the Vatican in Rome in 1509-1511, just around the corner from the Sistine Chapel ceiling, which Michelangelo painted from 1508-1512! In that fresco, the women surround Apollo, who plays not a classical lyre (as occurs in Raphael’s early preparatory drawings) but a Renaissance lira da braccio! The idea of including a contemporary instrument was probably Raphael’s. Giulio Sanuto has inserted the Muses from Raphael’s fresco, but it is as if Apollo left their midst, traveled right to compete with Marsyas, then came to the center sheet to flay him, and then can be found a third (fourth?) time in the back middle ground of the left sheet.

That is the moment where Apollo, recognizable by the leonine locks and the cloak, forces donkey ears onto Midas under his crown under Minerva’s supervising gaze. Midas, too, protests with his arm, grasping up against Apollo’s and seems to be crying out. Apollo looks at the placid Minerva as though for approval, his glance like, am I doing this right? In flamboyant earlier Renaissance fashion, Apollo’s cloak flies up behind him as Minerva’s skirt and hair floats away from her. I think this also indicates that as gods, they were not necessarily bound by such earthly qualities as gravity.

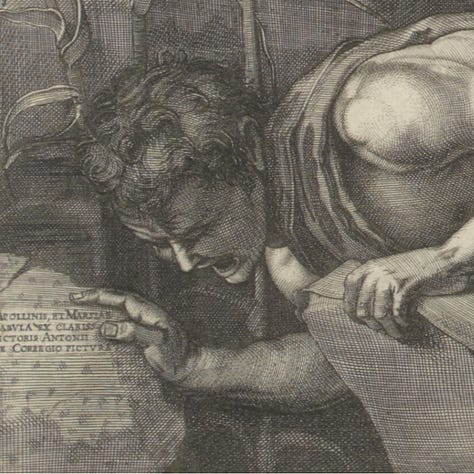

But then, in the foreground, we have another nude male figure we have not seen before, twisting in a strangely uncomfortable-looking position, who leans over a cliff screaming into the void below. You’ll remember from the story that this is King Midas‘s barber, telling the secret of King Midas‘s new donkey ears to the river, where it gets picked up by the reeds, here looking for all the world like stalks of corn. This may be another reference to New World imports, which we talked about last week, because corn was introduced in Europe during the 16th century. But it could also be some other marshy reed that I don’t recognize. Nevertheless, they are certainly tall enough to lift the barber’s secret into the wind where it was circulated far and wide.

It was this figure of the barber that I first recognized as a quote in this print: his expression with the wide mouth and the anguished, scrunched brow is immediately recognizable from several copies after Leonardo‘s Battle of Anghiari. The way he grips the cliff edge quotes the jagged lower edge of the shore in the Battle of Cascina by Michelangelo composition, even though we can’t even see any water below the barber—but because we know the story and the quote, we can tell what is going on. His pose isn’t a direct quotation that I have found, but the twisting Michelangelesque body still foregrounds the pushing of elbows and the foreshortened jutting of knees.

I haven’t yet come to the purpose of this print, really, and I’m sure you have more questions. Why did Giulio Sanuto want to show off his art-quotation skills in such a large, ambitious format? And isn’t that Venice in the background? I’ll come back to these questions next week! Meanwhile, you have homework: it’s easy, I promise. Look back at my post November 1 about significant vs. non-significant representation across the edges of a multi-sheet print. How would you describe the joins between papers in Giulio Sanuto’s Apollo and Marsyas (Look at Figure 1 again), and do you think the joins are successful in making a unified picture, or not?

Next week I’ll also tell you about another “hidden” Renaissance musical instrument in this artwork…but for now, please enjoy two short concerts on Renaissance lira da braccio and shawm!

Aline Hopchet on a Renaissance shawm:

And Baptiste Romain on Lira da braccio! Note all the enharmonic strings:

*I’m being linguistically silly because it is ever so much worse than silly to glorify battles, let’s never do that again, please.

**There was also a conflation with a musical competition between the god Pan and Apollo, depending on the sources, but I’m keeping it simple here to match the story pictured—but this may explain why Marsyas doesn’t necessarily look like a satyr here.

The shawm looks and sounds like the one used by "snake charmers" in the cartoons of my youth.

The radish greens is an interesting choice for a groin cover for Marsyas. Was it just the convention to not include genitals in art back then or would the artist get in trouble?