June triple-header!

New-to-me artwork celebrating Summer Solstice, Pride Month, and Juneteenth

Today is the summer solstice, yesterday was Juneteenth, and June is pride month! It’s a busy moment, holiday-wise. So while I polish my upcoming promised post on Titian’s Ca’ Pesaro Altarpiece, let me meanwhile delight you with close looking details from three new-to-me artworks. It’s a good reminder that there will always be more amazing artworks to discover.

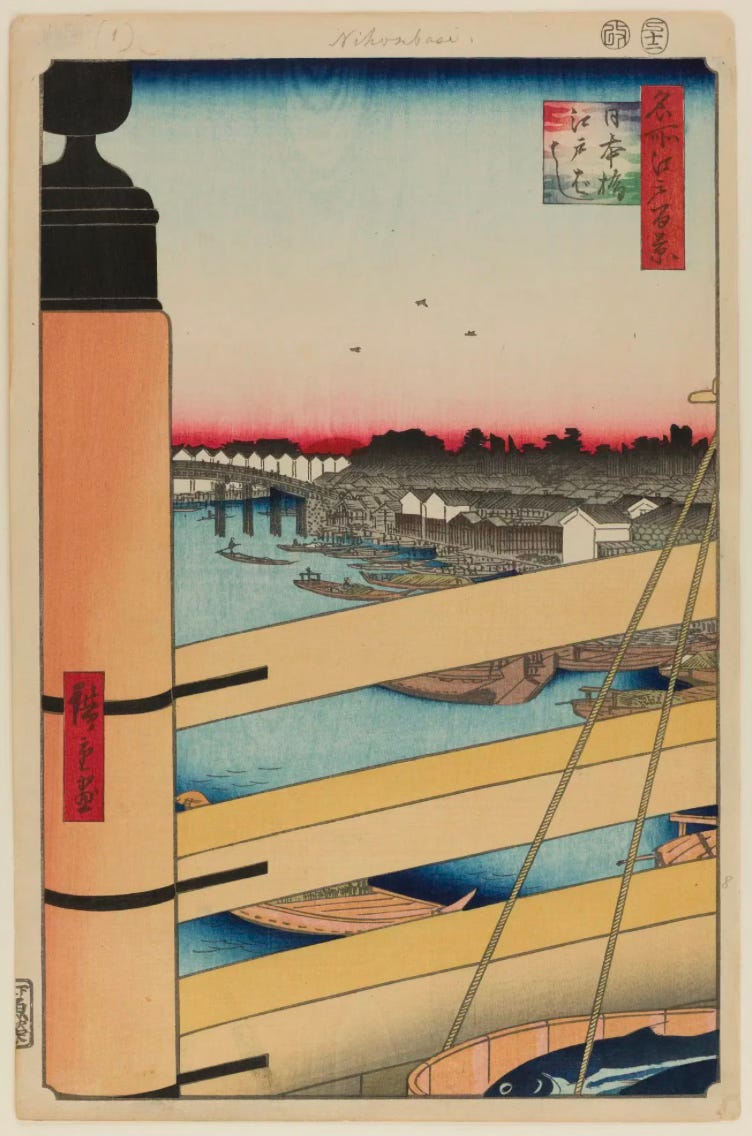

The first, Nihonbashi and Edobashi Bridges, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo by Utagawa Hiroshige (Japan,1797-1858).

Hiroshige often contrasted a large detail in the front with a far view deep into a landscape (a technique admired and adopted by late 19th century French painters, as you’ll remember from my post dated September 20, 2024, which uses as one example a print of fish-shaped lanterns on a bridge by Hiroshige). Here we have a distant small view of the Edobashi bridge seen beyond an enlarged finial post and railing of the important Nihonbashi bridge. Fishing boats arrive at the market, just at the moment where the rising sun glows round and red, spreading its intense glow across the horizon.

It’s the first day of summer, or thereabouts. We know this because of the detail that took me more than a moment to notice: a wooden barrel of fish—lower right hand corner—held up with taut ropes tied to a pole, that someone is transporting over the bridge. It’s the expensive skipjack tuna, the bonito, that signals the arrival of summer—since that is when it becomes available.

Note also the grain of the wood of the block carved for this image, brought out in the intense blue at the upper edge of the print, as the sunlight pushes back the night. Happy Solstice!

Second: Rainbow Harp of 1985 by Robert Rauschenberg, for his Rauchenberg Overseas Culture Exchange (ROCI). I wrote more about this important artist in my post of April 12, 2025, and you can read more about his life and relationships at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation website. I love the multicolored threads of this sculptural combine work, suspended from a frame; the striations within a frame evoke the parallel strings interior to a harp frame.

Note the added turquoise and skull too, valuable and aesthetically-intriguing added objects. It’s as though they, stone-like, hold the rainbow idea down from the sky, or perhaps they are a treasure at the end of the rainbow. As a rainbow-loving queer harpist, I was tickled to learn about this artwork recently! You can almost see and hear the doi-oi-oing of the wire sproinging wildly out at the top, which reminds me of the loose ends of a new, untrimmed harp string.

If that isn’t enough rainbow for you, here is another more rainbowlicious work from the same year in the same series, the Caryatid Cavalcade I.

Happy Pride!

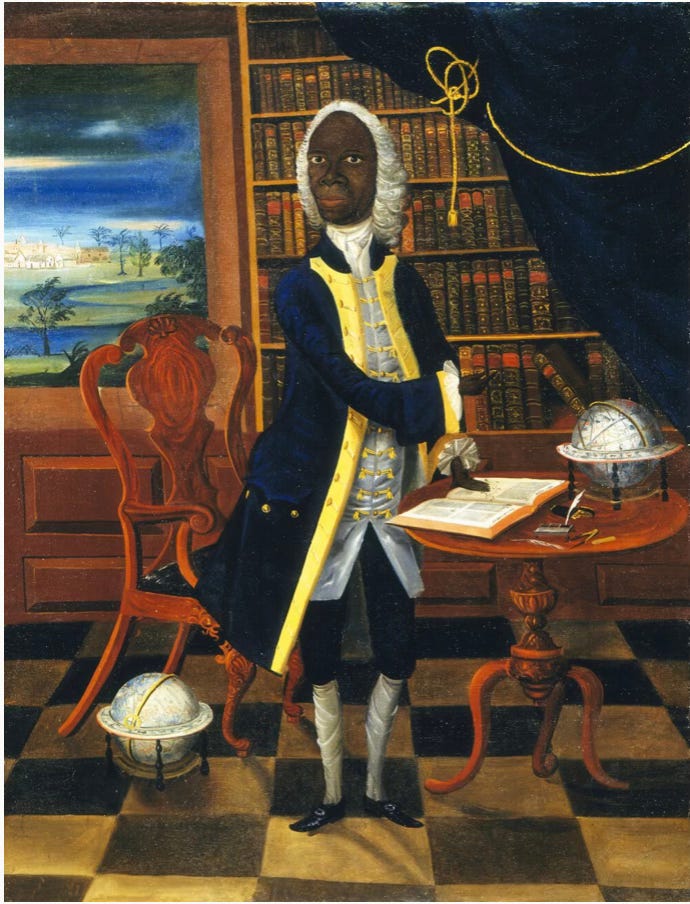

Third and most astounding: this example is actually a recommendation of an article a friend sent to me, and absolutely worth a slow read, about the power of close looking at a painting (including scans and early photographs) to elucidate history. It’s a fascinating tale, the result of years-long research by Fara Dabhoiwala, published in the London Review of Books. This 18th century painting may not have the painterly qualities of, say, a contemporary Joshua Reynolds portrait, but instead offers clues to the library, social class, and intellectual pursuits of the subject, Francis Williams.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n22/fara-dabhoiwala/a-man-of-parts-and-learning

To give you a short summary of the article: Francis Williams was born the son of enslaved Africans on a Jamaican plantation, but his parents achieved their freedom and earned enough money to send him to England for an education—as well as to own a plantation with slaves themselves (a good reminder about the complexity of colonial history).

After 15 years in Europe, studying at Cambridge, gaining a reputation as an art collector and a scientist, and being considered for admission to the Royal Society, FW inherited his parents’ plantation and returned to Jamaica. Later in his life, he hired a sailor-painter named William Williams (no relation!) to paint his portrait—on the occasion of one of his great astronomical observations.

William Williams’ style (at least this early style, but I think there are still gaps and unanswered questions about his oeuvre ) meant that the virtues of this painting are about including details such as book titles, a globe, and the night sky, that showcase the penetratingly inquisitive scholarship and world-class erudition—and I’m talking admired by Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley—of the portrait sitter. Or in this case, somewhat unusually, a stander, FW having risen from his chair. I think that standing gives the gentleman a verve, metaphorically portraying his active mind.

This painting is dateable by the book collection pictured, and open to a page of Newton’s Principia, showing a diagram about how to calculate the gravitational workings that would bring back a returning comet—in other words, proving the anticipated reappearance of Halley’s comet. Out the window of Francis William’s study in the painting is that appearance of Halley’s comet, viewed in relation to the constellations appearing above Jamaica at the time. Which appearance FW was erudite enough to understand and predict! No wonder he wanted to commemorate that achievement with a painting. Wow.

Again, the image may be off-putting because of its naïveté of style, which is partly an accident of history—FW was in Jamaica and probably hired the only portraitist who was coming through town.

Dabhoiwala says it is amazing that this painting was not lost in the intervening years, particularly given the abhorrent attempts to belittle Francis Williams’ (and by extension all persons of African descent) intellectual capabilities. But I think it sometimes happens that a person is so greatly admired, in FW’s case intellectually and scientifically, that they become a legend for the next several generations—and that despite the racism of the centuries between this painting’s date in 1759 and its rediscovery, no one who owned this painting could bring themself to get rid of it, because of the oral histories handed down about this man.

In short, perhaps it was the force of personality OVER the aesthetics that allowed this painting to survive. We can only wonder and grieve at how many other talented and brilliant individuals, oppressed under slavery and its ugly aftermaths, have been forgotten, and how remiss we would be to continue to forget.

Juneteenth is about remembering. Happy Juneteenth!

thanks to my dear friend Aaron Friedman for sending me this Fascinating article! Which reminds me: Happy Make Music New York day and Fete de la Musique! Go play some music this weekend!

The Rauschenberg piece reminds me of African strip-woven cloths.